614

614  6 mins

6 mins Freda Huson, Hereditary Chief of the Wet’suwet’en. She was awarded the 2021 Right Livelihood Award for fearless dedication in leading a peaceful fight against a pipeline which would have disastrous consequences for her people.

Some context

British Columbia, Canada 2019.

After more than 7 years of planning, TC Energy was ready to begin the construction of the Coastal Gaslink pipeline.

The pipeline is at the centre of a $40 billion project – the largest single private sector investment in Canada’s history.

It would cut across the entire province, snaking 700 km through BC’s forests, remote regions and rugged mountains.

The pipeline would be the beginning of an “energy corridor” carrying fracked gas from near Dawson Creek in the east to a conversion plant at the Pacific Ocean port of Kitimat.

Once converted into liquified natural gas (LNG) it would be exported to global markets.

However, one-third of the pipeline’s planned route would take it directly through 22,000 square km of unceded land belonging to the Wet’suwet’en people.

The Wet’suwet’en, a First Nations people, have never surrendered this land to the Crown.

Pushing forward and pushing back

The Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs do not agree to the proposed pipeline route.

Its route would adversely impact their lands, rivers, and way of life.

Hereditary Chiefs have proposed alternate, more acceptable pipeline routes through their territory.

But these proposals have been rejected by Coastal GasLink as too costly or environmentally risky.

So without their consent, plans to begin the construction of the pipeline on the Wet’suwet’en lands moved forward.

This has sparked local and nationwide protests, including anti-pipeline blockades that have paralyzed the nation’s transport infrastructure.

Many people have been arrested, and the police have received authorization to use deadly force against the land defenders.

At the heart of the protests is the non-respect of a fundamental right of Indigenous peoples. It is known as free, prior and informed consent (FPIC).

FPIC is enshrined by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

It grants Indigenous peoples the right to give or withhold consent to projects that impact them or their territories.

The Hereditary Chiefs will not give their consent to the route of the Coastal GasLink project.

“What is continuing to happen today

is what has happened for hundreds of years.

Government gives out permits

and allows industry to proceed with projects

which destroy water, land, and the way we use our land.”

Freda Huson

A brave visionary

Freda Huson, a female chief (Dzeke ze’) of the Wet’suwet’en, has become the well-known face of the opposition to the pipeline.

Her efforts in fighting the pipeline were recently recognized by the Right Livelihood Award. This international award, established in 1980, “nurtures a growing community of brave changemakers, connecting them and their solutions, worldwide.”

Freda Huson received the 2021 Award for her “fearless dedication to reclaiming her people’s culture and defending their land against disastrous pipeline projects.”

Image: Chief Freda Huson (Courtesy Unist’ot’en Camp – Facebook)

“Even though I’m being recognized – it’s not all me.

It took hundreds of people to make it all happen.”

Freda Huson

Back in 2010, she built her home, a log cabin, and established the Unist’ot’en camp on lands now at the centre of the dispute with Coastal GasLink.

Since those humble beginnings, the camp has grown.

In 2015 a healing centre was set up, and the camp became a place where First Nations people could come to learn and heal through traditional ways.

The camp’s activities have continued to expand and now include treatment for addictions, women’s groups, cultural workshops, and language schools.

All the programs and the actual running of the camp depend on the traditional use of the land.

This includes hunting, trapping, gathering medicines, berry picking, and visiting cultural ceremonial sites.

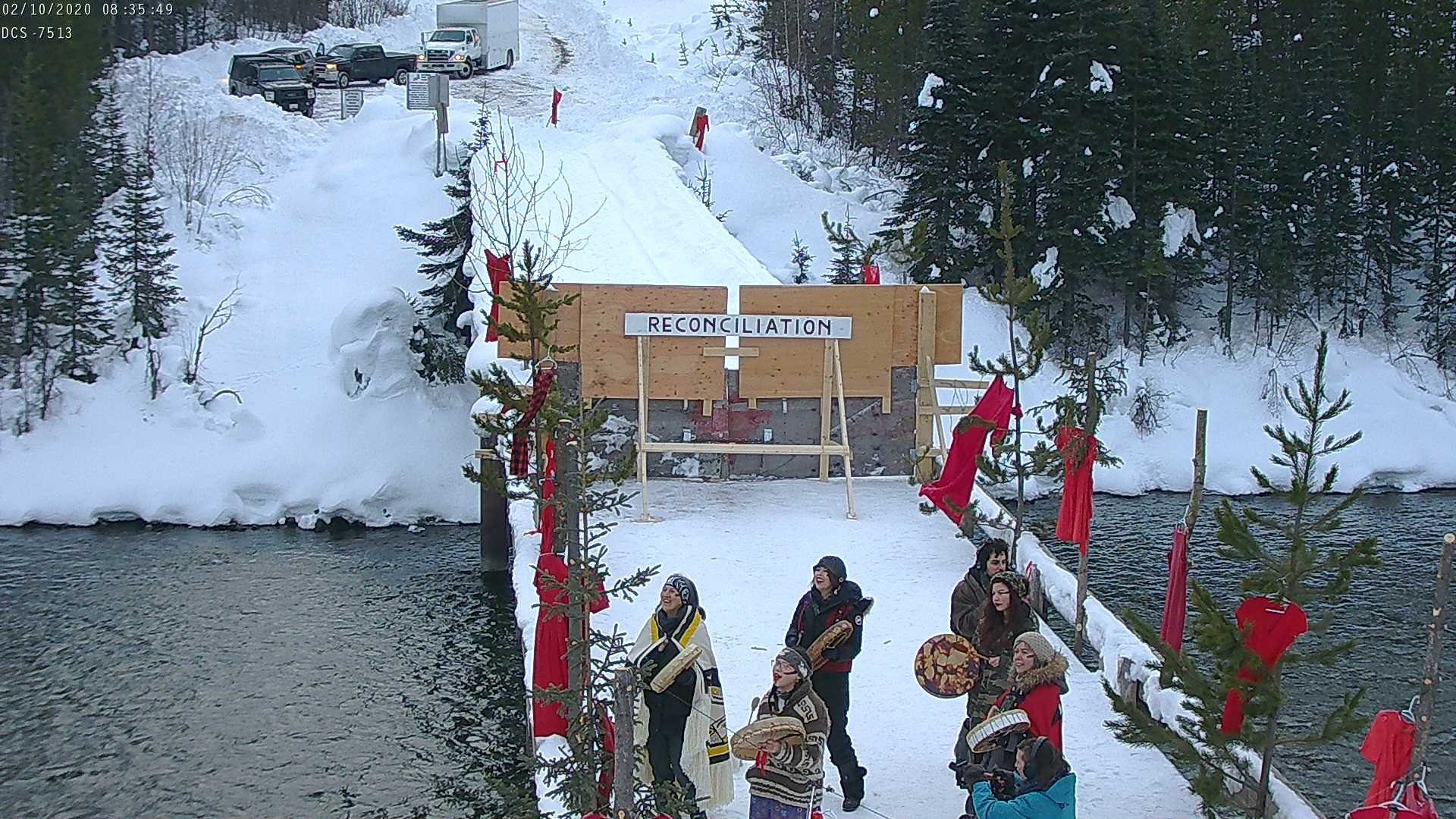

Camp access

The camp accepts visitors, but free, prior, and informed consent is required to enter the land.

It’s an ancestral tradition – visitors are asked to identify themselves and their relationship to their hosts at an access checkpoint located 20 km from the camp.

The camp’s website explains that FPIC ensures peace and security on the territory.

“That (access) gate is for our protection. We had racists coming in and shooting rifles, ramming my gate with vehicles, and using explosives to blow up my gate,” explains Freda Huson in a Facebook video.

Since its establishment, the access point “has hosted gatherings, workshops, and traditional activities for Wet’suwet’en and provided an essential space for Wet’suwet’en to reconnect with their traditional territories.”

Border crossing

However, the access checkpoint also acts as a territorial border crossing.

Since the beginning of the Coastal GasLink project, the checkpoint has been used to deny access to the portion of the pipeline project located on Wet’suwet’en land.

By 2018, the checkpoint had become a place of near-constant confrontation between the land’s defenders and the police.

The confrontations boiled over in February 2020 when the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) used force to dismantle the checkpoint.

The RMCP was enforcing a court injunction that allowed the Coastal GasLink Pipeline to access the land.

“RCMP are climbing the snow towards gate entrance, telling all present they will be arrested and face civil or criminal contempt. Matriarchs are calling the ancestors. There are only women here besides one male media and one male indigenous supporter. ” Image courtesy Unist’ot’en Camp – Facebook

Freda Huson, Brenda Michell, also a Chief and Freda’s sister, and Dr Karla Tait, Freda’s niece and director of the healing centre, were among the many arrested during the early days of February.

“I’m here now because this is my home,

this is where I live…

This is an unjust system that we live in.

My people have been pushed aside,

pushed aside for hundreds of years.

And it hasn’t stopped; it’s still happening right now.

My people live off these lands.”

Freda Huson

Numerous protests supporting the Wetʼsuwetʼen have since broken out across Canada following the RCMP’s actions using “heavily armed tactical teams, division liaison personnel, regular uniformed officers, canine units, helicopters, drones and snowmobiles” according to CBC News

What comes next

It is an unequal fight.

But the struggle to protect the traditional Wetʼsuwetʼen territories for future generations goes on.

“We have only something like 10% of our traditional territory remaining. That’s the reason we are fighting so hard to protect that last 10%. So that we can continue to have clean water, continue to have salmon, continue to hunt our moose, collect berries and medicines.

Because that’s who we are as Unist’ot’en, Wet’suwet’en, the land sustains us.

If we don’t take care of the land, we won’t be able to sustain ourselves.”

Over time, support for their cause is growing.

“The key that helps us through is being peaceful

and finding different kinds of measures and solutions

to the unfairness that we are finding every day…”

Freda Huson

International Response

The UN Committee charged with Eliminating Racial Discrimination (UN CERD) examined the situation in 2019.

The CERD formally informed Canada that it was “disturbed by forced removal, disproportionate use of force, harassment and intimidation by law enforcement officials against Indigenous peoples who peacefully oppose large-scale development projects on their traditional territories.”

Furthermore, the committee was “alarmed by (the) escalating threat of violence against Indigenous peoples.”

As a result, the UN called on Canada to immediately “halt the construction of the Coastal Gas Link pipeline in the traditional and unceded lands and territories of the Wet’suwet’en people, until they grant their free, prior and informed consent…”

The CERD also wants Canada “to prohibit the use of lethal weapons, notably by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, against Indigenous peoples.”

In November 2021, a request to the CERD for urgent action was submitted by a coalition of Indigenous rights, human rights, and environmental experts.

They requested that the UN intervene in the repeated human rights violations against Indigenous peoples and hold Canada accountable for ignoring the 2019 UN directive.

Likewise, the group also sent a letter to Prime Minister Trudeau asking him to respect the rights of Indigenous peoples and the terms of the UN Convention.

The Right Livelihood Award

In accepting the Right Livelihood Award, Freda Huson reflected on how the Wet’suwet’en struggle was part of a larger fight.

She hoped the Award would give her people the opportunity to “join forces with many other people who have done similar things (to what my people) are doing. All around the world (people) in many other countries are doing the very same things to protect the land and protect the environment and make sure that people are treated fairly.”

“The main thing we are doing is raising awareness of the injustices that are happening in Canada. Indigenous peoples are being forcibly removed from their land in the name of industry.”

“So if we make that connection around the world, hopefully, all of us together are stronger than individuals trying to fight. We are all fighting the same fight. “

“Our people’s belief is that we are part of the land.

The land is not separate from us.

The land sustains us.

If we don’t take care of her, she won’t be able to sustain us

and we, as a generation of people, will die.”

Freda Huson

For more information

Follow the Unist’ot’en Camp on social media on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram or visit their website and sign up for their newsletter.

Support the Wetʼsuwetʼen Hereditary Chiefs

Legal pressure is a key element of the Unist’ot’en struggle. The Unist’ot’en face expensive, unforeseen legal fees in the fight to protect their territory.

Visit the Action Network fundraising sites to make a financial contribution or check out their Supporter Toolkit for other ways to support them.

To learn more about FPIC see “Respecting free, prior and informed consent – practical guide for governments, companies, NGOs, Indigenous peoples and local communities in relation to land acquisition.”

Feature image credit – photo courtesy of The Right Livelihood Award and Freda Huson

If you enjoyed this article you may also enjoy reading about Cameroon’s first Right Livelihood Award winner Marthe Wandou. Through her work, Ms. Wandou is fostering of community-based child protection in the face of terrorist insurgency and gender-based violence in the Lake Chad region a)of Africa.

Quote This Woman+

Quote This Woman+ End FGC Singapore (EFS)

End FGC Singapore (EFS)