611

611  11 mins

11 mins The title of FILSAA’s video, “How to go to law school with a criminal record”, caught my eye.

I started thinking about it. I remember seeing movies where people in prison read law books and do legal research to help their cases. Nelson Mandela was a heroic example – studying law during the 27 years that he was in prison, eventually becoming the president of South Africa.

But the title raised other questions – wasn’t the idea behind creating prison systems to help people become law-abiding citizens? Why shouldn’t they be allowed to become lawyers? What was preventing them from becoming lawyers? Doesn’t “paying your debt to society” mean that you are free from further punishment once you’ve served your sentence?

And who exactly was this group that helps formerly incarcerated people become lawyers? I needed to know more.

Myth-busters… and more

I talked with Phil Miller, Laura Weiner and Matt Proper, three of the 5 board members of FILSAA – the Formerly Incarcerated Law Students Advocacy Association – to learn more about what they do.

FILSAA is a student association at the CUNY School of Law. It was started in 2018 by first-year law student Jerry Koch. Jerry was himself formerly incarcerated. He wanted to create a support network that helps recruit prospective students. He also wanted to provide academic and social support during law school. He advocated for easier transitions into the legal field for people who had been imprisoned.

Going to law school and becoming a lawyer can be intimidating for someone who has been in prison. There are so many barriers. Access to money, social support or academic resources are the most obvious. But the folks from FILSAA told me how the legal profession’s gatekeepers – law schools and bar associations – throw in an additional obstacle. It’s a hurdle that can be disastrous for a formerly incarcerated person. It’s the “Character and Fitness requirement.”

Photo by James Morano, courtesy of FILSAA

Character and Fitness

Applicants to law school and the Bar must answer several questions about Character and Fitness. These questions include any previous interactions with law enforcement. Question 26 on the New York State Bar application asks, “Have you ever, either as an adult or a juvenile (emphasis added), been cited, ticketed, arrested, taken into custody, charged with, indicted, convicted or tried for, or pleaded guilty to, the commission of any felony or misdemeanor or the violation of any law, or been the subject of any juvenile delinquency or youthful offender proceeding?”

Let’s break that down. Applicants are forced to disclose any interaction with the criminal justice system. It doesn’t matter if the incident ended in conviction. The justification and the outcome do not matter either – civil disobedience, mental health issues, substance abuse, or simply having been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

It is clearly intrusive and arbitrary. It is also discriminatory – it’s a question that disproportionately impacts people from the communities most affected by systemic criminal injustice.

Regardless of the circumstances, a “yes” answer to Question 26 can mean the end of someone’s dream to pursue a legal career. There have been several widely reported cases of the Character and Fitness battles of outstanding, formerly incarcerated candidates in recent years. It’s an issue that has a clearly chilling, disheartening effect on anyone previously incarcerated.

Changing an unjust system – from the inside, out

FILSAA wants to help formerly incarcerated people navigate these application processes. They also want to help them overcome the other obstacles they face in pursuing a legal career. They believe that people who have found themselves on the wrong side of the criminal justice system at one point in their life are precisely the people who should be empowered to take leadership roles in finding solutions to improve the system. Board member Laura Weiner says, “The law is a fundamentally conservative institution. But the law can be changed by lawyers.”

I was excited and wanted to learn more about their work and why they want more formerly incarcerated people in their field. I wound up discovering how they are actually reforming the U.S. criminal justice system from the inside, one lawyer-in-the-making at a time.

Let’s start from the beginning; how did FILSAA start?

Laura: FILSAA was started in 2018, by Jerry Koch, who was formerly incarcerated and in his first year of law school. He was having difficulties due to his personal experience reading case law. He felt like there wasn’t a lot of support or community around him, and his idea was to build the community that he lacked. That became this beautiful organization that we are all really grateful to be a part of today.

The two A’s in FILSAA stand for Advocacy and Association. FILSAA is really about connecting abolitionist allies with formerly incarcerated students.

And as a side note, Jerry just recently passed the Bar. He’s now a practising attorney in New York City.

I first heard of what you are doing on social media. You are doing many different things; for example, I saw that you have a YouTube library to help formerly incarcerated people apply for law school. Could you tell me more about what you are doing?

Phil: FILSAA has a range of actions. First, we spread awareness that formerly incarcerated people can become attorneys. There’s a big misconception that you cannot be an attorney if you have a felony on your record. We want to correct this and try to inform as many people as we can through flyers, activities, and speaking to groups with a large majority of formerly incarcerated people.

View this post on Instagram

Actually, our work can start before someone even gets admitted. For example, we help people studying for the LSAT, and we have a volunteer LSAT tutor who works with prospective students to help them improve their scores. Then, once law students are in school, we offer them support. Once they’re finally in law school, we continue to support them with outlines, books or advice. Although it’s not what it was officially called, FILSAA is a support network. Everyone involved becomes very close allies and friends, almost like a family. Everyone’s there to help.

Another thing we have started to do is offer a modest grant to formerly incarcerated students to supplement their summer internships. This depends on our funding, but we were able to give about a thousand dollars per person last year. This is because many of the internships undertaken in our law school are unpaid as they’re in the public interest field.

In the future, we also want to provide financial support for the Bar preparation courses when students are graduating. The Bar exam is such a huge, daunting task, and it’s also very expensive, so we want to see people succeed on their first try.

Lastly, we also have a Signal chat where everyone in our community can stay connected – from before or beginning law school all the way through to post-law school graduates. We all keep in touch and try to help every step of the way.

Do you work only with students or prospective students of CUNY or do your activities expand beyond the school?

Laura: We are pro-CUNY, being CUNY students ourselves. And CUNY is particularly open to accepting folks with records, but we can help anyone. We have a Gmail address, which is open to anyone. We’ll respond to anyone asking about law school – we often get letters from people on the inside. We’re also part of a resource packet given to formerly incarcerated people upon release. One of our goals is to get a quorum of people across law schools who have experienced the system from that perspective.

From your point of view, what is the most important thing to know about FILSAA?

Phil: For me, it’s really important to spread awareness that you can be an attorney after spending time in prison. I was incarcerated for many years and I still have friends who are inside. I also have a few friends on the outside who were with me while in prison who are also considering law school.

Showing that this is a possibility is one of the most important things. Even when people hear of the possibility, it sometimes sounds like a distant rumor, “Oh yeah, I think I heard that someone became an attorney after prison.” But people aren’t sure; they don’t know that it is possible. So for me, living as an example of someone who was locked up for a very long time and is now in law school, spreading that knowledge is one of the most important things I can do.

Laura: I agree a thousand per cent with Phil. Our job is to make sure that folks are not only aware of it but they know the concrete steps they can take. It is really just a series of steps, and each is possible. On a macro level, the law is a fundamentally conservative institution. But the law can be changed by the people practising law. I think it’s essential that folks who have experienced the law from the other side – the oppressive, silencing side – be given this opportunity. The law can change, and I think it will change when we have many people who have experienced incarceration practising law. We need them as advocates. I believe that this is what we really need.

Matt: I agree with Laura and Phil, and I would add that, although CUNY Law is a bit different, law school is still an isolating and tough place to be. As FILSAA grows, I think it can be central to fostering community within law school by making sure that FILSAA stays true to supporting those in law school.

FILSAA group members – Photo courtesy of FILSAA

It sounds like very meaningful, impactful work. What have been some of the “big wins” in what you are doing? Could you tell me some more about the impact that you have seen?

Phil: I can think of one recent thing. It wasn’t a huge win for FILSAA, but it was a step in the right direction.

I had a meeting last week with the founding partner of a personal injury firm where I am interning right now. He has agreed to make an official internship for a formerly incarcerated member of FILSAA every summer. Concretely, it’s the opportunity for a formerly incarcerated person to get their foot into the legal profession while they’re still in school and get some experience. It’s a big step forward.

Matt: Another tangible development is that the admissions office at CUNY recently asked one of our previous co-chairs, Colby, to talk to them about how they can be more conducive to getting more formerly incarcerated people into the school and supporting them while they’re here. We are constantly badgering them, and Colby was finally able to speak with them – they got to hear his voice! That was a really exciting moment for FILSAA.

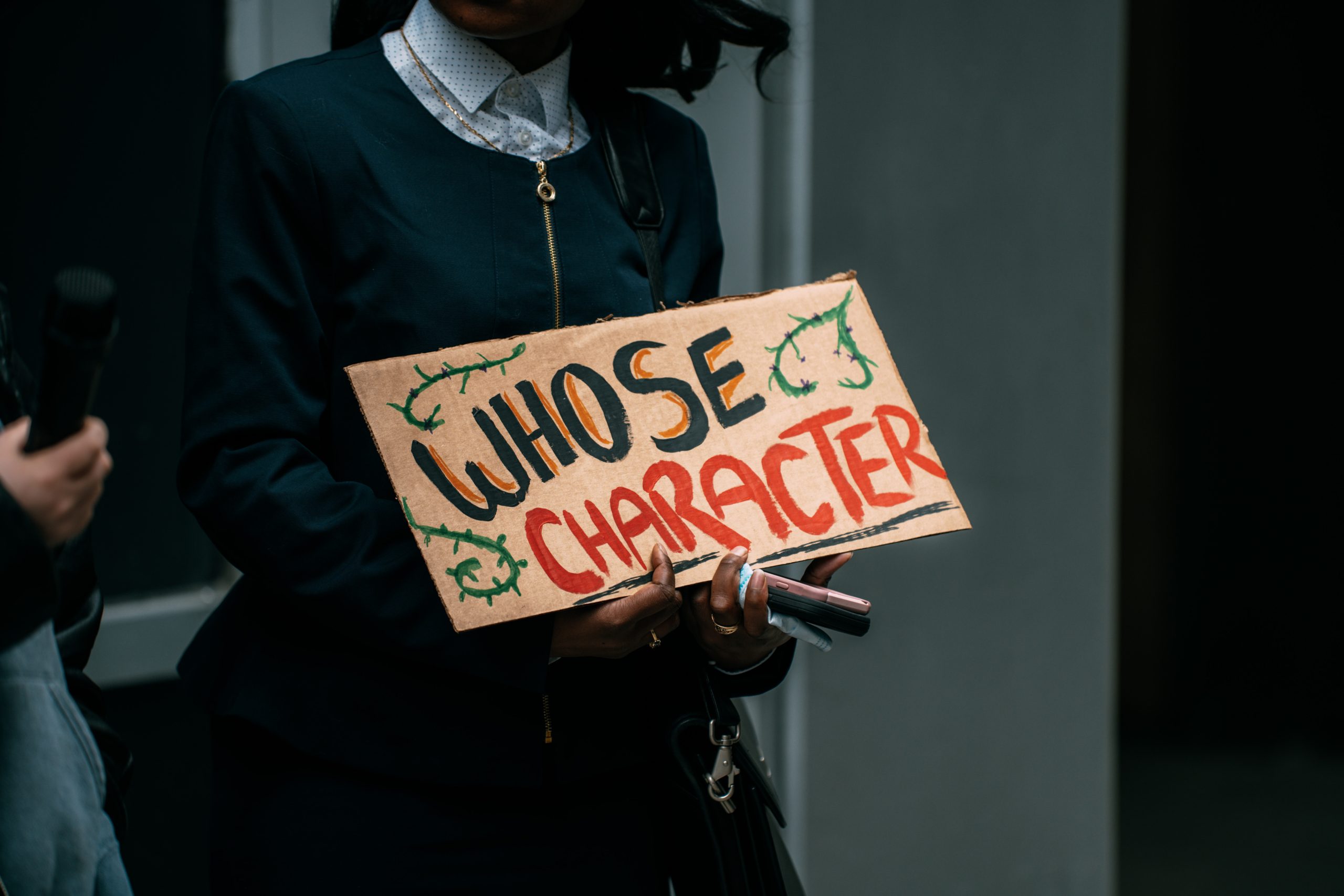

Laura: I also want to remember the “Unlock The Bar” protest just a couple of weeks ago. The three keynote speakers were Jerry, Colby and Phil. They each gave breathtaking, heartfelt, rousing personal speeches about the protest and about the gatekeepers of the law.

Here were three amazing humans who are going to be exceptional attorneys. I was very proud of FILSAA at that moment. We have created this community, and the individual members of this community are all really amazing.

Editor’s note: Unlock the Bar is a coalition of lawyers and law students advocating in New York for a just and equitable legal profession. Their goal is to dismantle the barriers to entry into the legal profession created by the Character and Fitness application. Specifically, they are asking New York State to eliminate all questions about involvement with the legal system, including criminal records, family court involvement, debt, and more. The ultimate goal is to eliminate the Character and Fitness application altogether in favour of a process that does not apply a carceral mentality to evaluating lawyers.

A FILSAA Unlock the Bar event in NYC – Photo by James Morano, courtesy of FILSAA

Could you tell me more about what it is like for a formerly incarcerated person who wants to pursue a career in law?

Phil: If you’re a formerly incarcerated member of FILSAA, one of the biggest challenges will be the Character and Fitness Committee. They are the gatekeepers of the legal profession in pretty much every state. Getting past them is doable, but it’s a huge hurdle, and it’s no walk through the park. You have to convince them that you are completely rehabilitated and no longer the person you were back then. The way they go about it is very invasive and abrasive at times.

And they don’t always say yes. Some attorneys have been denied a few times.

I’m hoping that I get it on the first try, but that’s still a huge problem that formerly incarcerated members will face.

Also, many law schools in New York, and probably everywhere, especially the elite ones, tend to exclude formerly incarcerated students from admissions. One of the reasons is that they doubt that a formerly incarcerated student can get past the Character and Fitness Committee for the Bar. It’s totally ridiculous to stop someone in the beginning because of what they assume about the future. So, that’s another challenge, but it’s something that we will continue to work on. We have a five-year plan to get rid of the Character and Fitness section for the bar exam. But we also need to change the minds of law school administrators everywhere and get them to understand the value of having formerly incarcerated students.

Laura: There is also a logistical challenge for people on the inside – they often don’t have internet access. There is a very arduous task called the LSAT exam to get into law school.

Editor’s note: The LSAT is a standardized test administered by the Law School Admission Council for prospective law school candidates.

You also have to have a bachelor’s degree to apply to law school. Those two obstacles alone make it difficult for people on the inside to apply to law school right off the bat.

It’s a real challenge.

Think about how it could be if folks on the inside had more internet access and access to higher education.

You mentioned that you have a five-year plan. Tell me more about where you see FILSAA going.

Phil: FILSAA moving forward is a continuation and expansion of everything we’ve mentioned. I would like to see many more members in FILSAA, more formerly incarcerated students in law school and many more entering the profession, passing the character and fitness committee. And I’d like to see this spread out beyond CUNY law.

I have a friend who just started Yale law school last semester. He was locked up for 17 years with me. He had to go through some hoops to get into law school. He’s in there now and doing fine. I would definitely like to see this spread to the point where whether or not you’re formerly incarcerated is no longer “a thing” if you want to go to law school.

Our tagline is “inspiring people, inspiring people.” I reached out to talk with you because we consider you to be very inspiring people, and I’d like to ask who inspires you?

Laura: One of the people that I find the most inspiring in my life is Kenyatta Emmanuel. He’s a fantastic musician and an amazing person. He spent many years incarcerated, and he has a really kind character and an amazing story. Every time I talk with Kenyatta, I am uplifted.

So that’s who I would choose, and you can also find him on YouTube.

Phil: My choice is similar to Laura’s, although it’s not a specific person. I’d have to say that it’s all the people I was with in prison. Many of them have higher aspirations they are trying to reach, and many of them come from communities where there isn’t much inspiration or any role models to aspire to.

There is so much stigma on the outside about formerly incarcerated people. Getting a job is difficult because as soon as someone sees the criminal record on your background check, they get rid of your application. Or they find some other reason to say “no.”

People inside know this. It’s like a shadow of despair in your mind that floats over your entire future. So for me, what I find inspiring is the people left behind. Their hopes, their dreams, the ones who still reach out to me, who still stay in touch via mail.

And I have to say, knowing that they’re out there rooting for me, not necessarily because I’ll make it better or forge a path for them to follow my footsteps, but just because they genuinely care about me and my success, I don’t want to let them down.

They inspire me to keep going.

Matt: That was… that was really nice, Phil. Law school can be an isolating thing. It’s an institution organized to take the person out of the law, sanitize it, and make it seem like the law is a neutral, objective thing that governs society. But in reality, it’s just the opposite. The people are what is essential at the end of the day. Being a part of FILSAA and being around the people who make FILSAA happen every day inspires me.

The community that FILSAA creates, both for those who are formerly incarcerated but also for everyone, is just so inspiring.

(Portions of this interview have been slightly edited for clarity.)

Feature image: Photo by James Morano, courtesy of FILSAA.

For more Information on FILSAA

Check out FILSAA on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or Youtube.

For more information, or you are a formerly incarcerated person applying to law school, contact them at the email cunyprisonabolition@gmail.com or make a donation to help formerly incarcerated law students.

Give Your Best

Give Your Best https://www.goldmanprize.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Kimiko-Hirata-Photo_Goldman-Environmental-Prize-09-scaled.jpg

https://www.goldmanprize.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Kimiko-Hirata-Photo_Goldman-Environmental-Prize-09-scaled.jpg